|

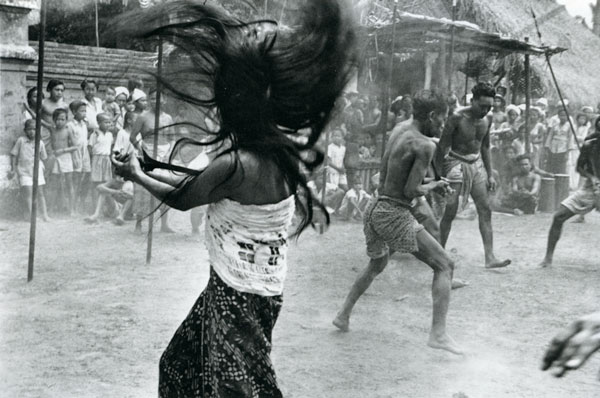

Henri Cartier-Bresson Batubulan villagers entranced during a Barong performance, Bali, 1949. |

John Bloom

Photography has conventionally been portrayed as a recorder of facts. It has also been treated as a servant of appearance, its images placed in the category of scientific knowledge. But photography is something other than a recorder of facts.

The fact that photographer and camera select segments of a continuous world suggests that the image may be just as much about absence - that not seen in the image - as it is about what is presented. The camera's instant, fully formed image is a facsimile that induces the viewer to forget real time and space and accept, instead, its illusion. Just as the world of spirits is as alive in the culture of Indonesia as the physical landscape, so too is the metaphysical reality that lies behind or adjacent to appearance in the photographic images made there throughout the past 150 years.

The credibility and power of Henri Cartier-Bresson's images are based upon his capacity to hold the rules of reality in suspense and to convince us of their irrelevance in the face of artistic truth. This capacity allows him to photograph ecstatic trance dances in almost the same breath that he reports on the political realities of a burgeoning independent nation. For him, these are extremes of human ritual which, because of their inherent experiential realms, demand different visual representations. The camera is simply the instrument that responds to his sense of the meaning of what occurs before him. Based upon the consistent intensity of his images, meaning is something othet than the fact of appearance.

Henri Cartier-Bresson was born in Chanteloupe, France, in 1908. He became seriously involved in photography in 1930, while recuperating from an illness. He had been exposed to Cubist painting and to the work of the Surrealists prior to his photographic career; both art movements, as well as early cinema, were to have a profound effect upon his vision. He was also influenced by the photographers Eugene Atget, Man Ray and Andre Kertesz. In 1932, Cartier-Bresson had his first exhibition of photographs at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City and published his first photo-reportage in the French magazine Vu.

The following year, he began using a 35mm Leica, and with its immediate response to his intuitive vision, he brought a new impulse to photojournalism. Images a la Sauvette (The Decisive Moment), the title of his most influential book, published in 1952, became the term given to his style, which is characterized by dynamic composition and a profound understanding of human psychology.

In 1935, he studied cinematography in New York City with Paul Strand; he returned to France in 1936 to work with filmmaker Jean Renoir. In 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, he made a documentary film, Victoire de la Vie, on the conditions in Spanish hospitals. Drafted at the outbreak of World War II, he was captured by the Germans in 1940. During his imprisonment, his Indonesian wife, Ratna, sent him a Malaysian dictionary and they were thus able to communicate secretly in her native tongue.

Cartier-Bresson escaped from prison in 1943; and, later that year, he organized photographic units for the French Resistance to document the German Occupation. In 1947, with Robert Capa, George Rodger and David Seymour, Cartier-Bresson founded Magnum Photos, a cooperative picture agency. Throughout the remainder of his long and prolific career, he has traveled internationally to document important political and cultural events. Much of this work is characterized by a revelatory understanding of the relationship between people and their environment.

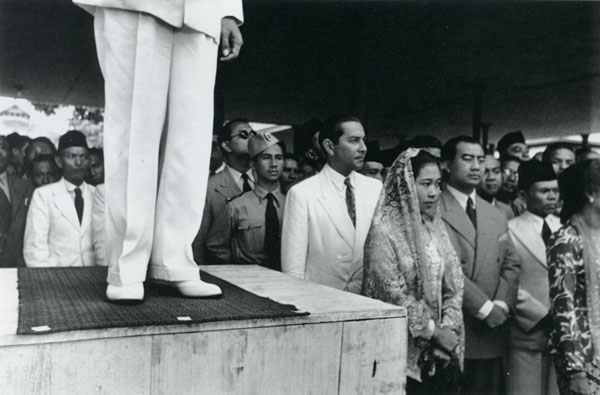

Indonesia held a special attraction for Cartier-Bresson since his wife is from Java. This personal link added depth, cogency and cultural sensitivity to an already existing alignment he held with the emerging independence movement headed by Sukarno. He had photographed in India both during its struggles to transcend a colonial past and at the sanctioning of its statehood after World War II. He recognized a similar political situation in Indonesia in 1949 and 1950. As his photographs of political speeches, rallies, departing Dutch soldiers and returning guerrillas show, he had a profound sympathy for the newly forming democratic state.

With the sheer beauty of the Indonesian agricultural landscape as a backdrop, Cartier-Bresson has photographed two quite separate realities in his portrayals of Sukarno's political campaigning and Balinese trance dances. On one level, they are complementary in the sense that the rhythms and changes of politics are a kind of superstructure that has little effect upon popular cultural and spiritual practices.

Without text and an historical perspective of politics in a colonial country, the apparent self-inflicted violence of the trance dance— the expressionistic faces and intense gestures—makes the images of political change seem pale. Yet the faces and gestures mask a rather different reality. What appears to the onlooker as contortion and exhaustion is a ritualistic inner journey toward transcendence. Cartier-Bresson's images suggest this other reality through graphic configuration and the portrayal of support in those helping the dancers.

In the political photographs, Sukarno is seen happily campaigning from his shiny black car and speaking from a makeshift podium. The outward signs indicate an adopted political methodology and negate the kind of communal reality that lives within the popular culture. The servants are happy removing the Dutch artifacts from the palace, and the Dutch soldiers seem more than happy to be leaving. If there is a tension in these pictures of independence, it is that so much of what remains evident is Eurocentric in origin—including the new political order.

Cartier-Bresson himself noted his observations about the conflicting bases of the "new" politics and the existing social order in his notes to his Indonesian photographs: What makes Bali outstanding and unique in this confused world is the harmony between the beliefs of the Balinese, their life and their expression. The cosmic harmony of their religious belief to which every act of their life is related; the social structure of the village which is based on cooperation of all the members instead of competition. A wonderfully frugal life in which the entity of the village is absolutely self-sufficient, in which everybody is an artist in the same time as a man working.

This harmony endured many years of outside influence, Dutch colonization as well as Japanese occupation. Cartier-Bresson's pictures of the trance dancers convey a sense of the enduring tradition that seems outside western experience. His pictures of the independence movement, of the rise of Sukarno, however, are harbingers of the self-inflicted, disharmonizing effects that came as a consequence of entering the post-World War II political-economic world order as a sovereign nation. As an analogy to what Cartier-Bresson accomplished with his camera, Indonesia's decisive moment in history was also an act of forgetting.

|

Henri Cartier-Bresson Batubulan villagers in a tance holding sharp kerises to their bodies during a Barong dance, Bali, 1949. |

|

Henri Cartier-Bresson Wmoan deep in trance during a Barong performance, Batubulan, Bali, 1949. |

|

Henri Cartier-Bresson President Sukarno in front of a painting portraying young Indonesian freedom fighters, Yogyakarta, 1949. |

|

Henri Cartier-Bresson President Sukarno's inaugural speech at the Istana Negara, Jakarta, 1949. |

|

Henri Cartier-Bresson President Sukarno returns to Jakarta, December 1949. |

|

Henri Cartier-Bresson Dutch soldiers at Tanjung Priok Harbor preparing to return to the Netherlands, January 1950. |

|

Henri Cartier-Bresson Young Indonesian guerrilla soldiers return from the mountains, near Solo, Java, 1948. |

The Return of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Decisive Moment Oct. 22, 2014

For 62 years, only the most fortunate of photographers and photo book collectors could peruse Henri Cartier-Bresson's masterpiece The Decisive Moment. This is about to change as German publisher Steidl is putting the finishing touches to the book's first ever reprint

Within the canon of European photography books it would be difficult to find one more famous, revered and influential as Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Images a la Sauvette or, as the American edition is titled, The Decisive Moment. Upon its release in French and American editions in 1952, Cartier-Bresson received personal letters affirming its brilliance from the likes of Jean Cocteau, Alexey Brodovitch, Carmel Snow (then editor of Harper’s Bazaar), and Joan Miro. The French edition publisher Stratis Eleftheriadis (known simply as Tériade) claimed it was “one of the most satisfying books that [he] had had the pleasure of making.”

Its value as an out-of-print collectable has risen over the past few decades resulting in keeping this masterpiece out of the hands of many younger photographers. Finally, after 62 years, it is again seeing the light of day this December with a gorgeous facsimile from the German publishing house Steidl.Henri Cartier-Bresson had an early interest in the photo book as a public vehicle for his work. In a letter to Marc Riboud he wrote, “Magazines end up wrapping French fries or being thrown in the bin, while books remain.” As early as 1933, Cartier-Bresson had begun one of many different proposed book projects with the intent to publish something of a monograph, but all had failed to be realized for one reason or another. Aside from a small exhibition catalog for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Decisive Moment was Cartier-Bresson’s first real book.

Its value as an out-of-print collectable has risen over the past few decades resulting in keeping this masterpiece out of the hands of many younger photographers. Finally, after 62 years, it is again seeing the light of day this December with a gorgeous facsimile from the German publishing house Steidl.

Initial mentions of the project came in May of 1951 with an assistant at the Magnum Photos office in Paris gathering images for the literary agent Armitage Watkins to show to a possible publisher – Richard Simon of Simon and Schuster Publishing. By June, Cartier-Bresson was in his own discussion with Tériade in France about a French-American co-edition between Tériade and Simon and Schuster Publishing. By the end of that year, the photographer had begun mining his archives for the photographs, editing and sequencing them and by March of 1952, three copies of a dummy were prepared. It was one of these book dummies that Cartier-Bresson had shown to the artist who would design and paint the exquisite and notably ‘non-photographic’ cover boards – Henri Matisse.

The final edit of 126 photographs taken between 1932 and 1952 appear roughly chronological but divided in the book into two sections – the first section (with exception to two images) corresponds to the years 1932 to 1947 and comprising photographs from Western countries and the second (with one exception) between 1947 and 1952 with photographs made in the East – China, India, Indonesia and the Middle East. According to Clément Chéroux, who penned this new edition’s informative essay on the book’s genesis, Cartier-Bresson’s decision to break the sequence into these two sections also corresponds to the formation of Magnum Photos in 1947, and subsequently, a moment in the artist’s life when he decided to commit himself to photojournalism. The photographer and theoretician Minor White noted his own opinions about the book’s division, “In his early work, form often dominates content,” adding, “the early pictures show a man more involved with his personal world than with the outer world […] The later work shows a decided preoccupation with content, the human, social or political meaning – his outer world.”

On July 22, 1952, the book went to press and 10,000 copies (roughly 3,000 French and 7,000 English language copies) were inked in heliogravure by the best printers of the time: the Draeger brothers. The results were so outstanding that Walker Evans in his New York Times review wrote of the book’s “breathtaking quality.”

Three months later, the book was released to critical acclaim and solidified Cartier-Bresson as one of the great photographers of his time. In contrast with its solid reviews, the modestly priced $12.50 book sold only fairly in the United States at less than 100 copies per month of the 3,500 copies initially distributed to bookshops – a previously expected second printing was therefore cancelled.

Three months later, the book was released to critical acclaim and solidified Cartier-Bresson as one of the great photographers of his time. In contrast with its solid reviews, the modestly priced $12.50 book sold only fairly in the United States at less than 100 copies per month of the 3,500 copies initially distributed to bookshops – a previously expected second printing was therefore cancelled.

Even though the passing of time had established The Decisive Moment as one of the most important books of the second half of the 20th century, Cartier-Bresson himself had reservations regarding allowing a second edition and it remained out-of-print. It was Martine Frank, Cartier-Bresson’s wife who after long conversations with the HCB Foundation, Cartier-Bresson’s daughter and publisher Gerhard Steidl, decided that this 2014 facsimile should finally be published.

Like the original, this 2014 edition will be also published in French and English editions, both following the 1952 layout faithfully. “We were in the lucky position to have been able to scan a mint copy of the book from the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson,” says publisher and printer Gerhard Steidl.

One difficulty facing any modern printing is that the remarkable gravure process that marks the original is now virtually extinct. “The gravure printing from the 1950s to the 1970s was really the quality peak for printing photography books,”Steidl tells TIME. “Today this technology is practically gone, no machines exist anymore. I’ve researched and made test-prints over many years to hone an offset technology to get exactly the same look as gravure printing. We use a special screening, particular inks, and a printing formula which [remains] my secret.”

For new generations of photographers and artists who have missed out on experiencing many of the world’s important books first hand, it cannot be stressed enough how important this new edition of The Decisive Moment is for a contemporary audience. “Robert Frank’s The Americans and Cartier-Bresson’sThe Decisive Moment were published within a few years of each other in the 1950s and both books have since become the blueprint for the modern photography book,” Steidl says. “When you look at them, the design, the sequencing of the photos and the printing are – even 60 years later – much better than most of the printed books on the market today. My intention in reprinting both has been to analyze the contents of the books, the intention of the photographers, and to print them in exactly the same way, so the next generation can see how these fine books were made and secure the future of photography publishing.”

The Decisive Moment by Henri Cartier-Bresson will be published in Dec. 2014 by Steidl.

Jeffrey Ladd is a photographer, writer, editor and founder of Errata Editions.

France. Sunday on the Banks of the River Seine. 1938. Click here to enlarge image. Photograph: Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Cartier-Bresson's classic is back – but his Decisive Moment has passed

It’s the book that changed photography forever. But why republish The Decisive Moment after 62 years, when it cements such out-of-date ideas?

France. Sunday on the Banks of the River Seine. 1938. Click here to enlarge image. Photograph: Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Cartier-Bresson's classic is back – but his Decisive Moment has passed

It’s the book that changed photography forever. But why republish The Decisive Moment after 62 years, when it cements such out-of-date ideas?

“There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment,” wrote the 17th-century cleric and memoirist Cardinal de Retz, “and the masterpiece of good ruling is to know and seize this moment.”

Today, the idea of the decisive moment is synonymous with a certain kind of photography, exemplified by the great European master Henri Cartier-Bresson. He used the phrase as the title of his – and European photography’s – most famous book, published in America in 1952. (The simultaneous French edition was, intriguingly, called Images a la Sauvette – Images on the Run.)

Now, having long been out of print and beyond the financial reach of all but the most serious collectors (a French first edition will set you back £2,750) The Decisive Moment has finally been republished. Sixty-two years on, it still carries the weight of its initial importance – even if the notion of the decisive moment no longer holds sway as it once did; staged photography, conceptual strategies and digitally manipulated images have all but rendered it old-fashioned except to purists, photojournalists and street photographers.

That The Decisive Moment belongs to a different time is immediately apparent from its cover, which is not a photograph but a signature cut-out by Henri Matisse, who offered to design the cover when Cartier-Bresson showed him a dummy copy. (The cultivated Cartier-Bresson was also friends with Jean Cocteau and Joan Miró, who designed the cover for his book The Europeans three years later.)

Extraordinarily, given that he had taken up photography seriously in the early 1930s, The Decisive Moment was Cartier-Bresson’s first self-conceived and edited book – 1947’s The Photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson was a catalogue for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Having co-founded the now-famous Magnum photo agency in 1947 with Robert Capa and David “Chim” Seymour, Cartier-Bresson had travelled widely on assignments, most productively to India and China, by the time it was published. He was also more aware of the value of his extensive archive, which he meticulously trawled to select the 126 images included in the book.

It is divided into two chronological and geographical sections: the first spans the years 1932 to 1947 and is made up of photographs taken in the west; the second spans 1947 to 1952 and was shot mostly in the east. Today, a photographer is more likely to make the move from photojournalism into art (not least because that’s where the big money lies), but Cartier-Bresson took the opposite tack. As the curator Clément Chéroux points out in his essay for the new edition, the pre-Magnum Cartier-Bresson was obsessed with form, and creating his now signature style. Post-Magnum – and post second world war – he was driven to make images that mattered more in terms of their social and political rather than aesthetic import.

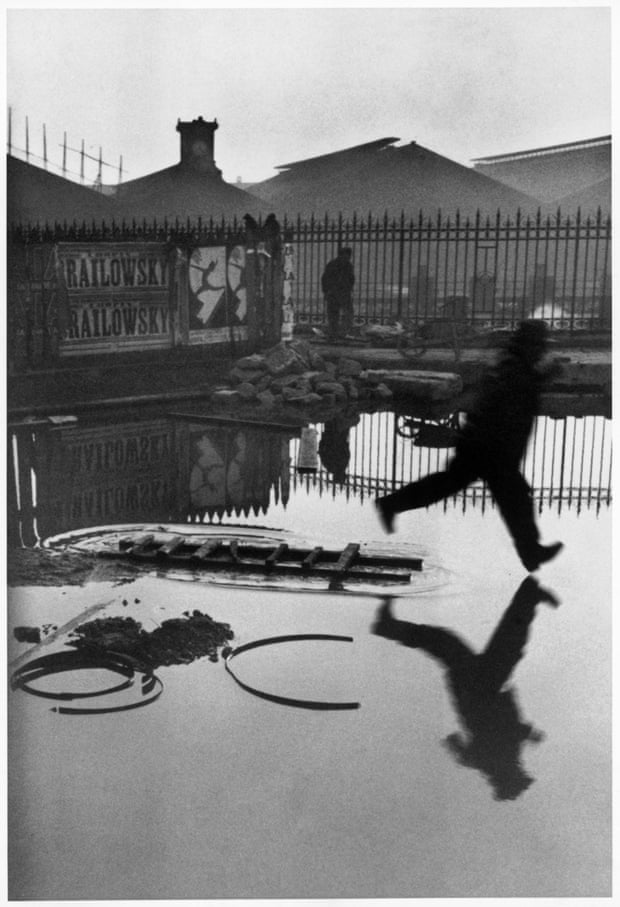

What The Decisive Moment did above all was enshrine the term in the collective photographic consciousness, shaping several ensuing generations of photographers. What Cartier-Bresson understood by the decisive moment is best explained by the famous quote from his lengthy introduction to the book: “Photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organisation of forms which give that event its proper expression.”

France. Paris. Place de l’Europe. Gare Saint Lazare. 1932. Photograph: Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Cartier-Bresson always emphasised the importance of composition, and liked to “instinctively fix a geometric pattern” into which a chosen subject fitted. The idea that he lay in wait for someone to walk into a precomposed frame may explain his extraordinary hit rate – but it runs contrary to the French title, Images on the Run, which suggests exactly the opposite.

Cartier-Bresson always emphasised the importance of composition, and liked to “instinctively fix a geometric pattern” into which a chosen subject fitted. The idea that he lay in wait for someone to walk into a precomposed frame may explain his extraordinary hit rate – but it runs contrary to the French title, Images on the Run, which suggests exactly the opposite.

The decisive moment has come to mean the perfect second to press the shutter. In this context, it might be better applied to, say, Garry Winogrand or Joel Meyerowitz, photographers who pounded the streets in search of the right convergence of light, action and expression rather than patterns and geometry.

In a thought-provoking essay in the London Review of Books last year, Gaby Woodwrote, “The reason his photographs often feel numbly impersonal now is not just that they are familiar. It’s that they’re so coolly composed, so infernally correct that there’s nothing raw about them, and you find yourself thinking: would it not be more interesting if his moments were a little less decisive?” Perhaps, but then he would not be the Cartier-Bresson we know – and his influence would not have been so widespread. Wood’s impatience may also be concerned with that lingering influence. Cartier-Bresson continues to cast a long shadow in the public, if not the contemporary photographic, consciousness. I would go so far as to say that, for many people with a passing interest in photography, he almost single-handedly represents photography: what it is meant to do and – more problematically for a generation of younger artists relentlessly questioning its meaning in an over-mediated world – what it is.

For me, what is interesting about the republishing of The Decisive Moment is that it has happened too late. The book is now a historical artefact. It cements an idea of photography that is no longer current but continues to exist as an unquestioned yardstick in the public eye: black and white, acutely observational, meticulously composed, charming. Colour and conceptualism may as well not have happened, so enduring is this model of photography outside the world of contemporary photography itself.

That Cartier-Bresson is historically important is not in question: he was a master, if not the master as his champions insist. But The Decisive Moment, despite its beauty and excellence, belongs to another photographic time in a way that, say,Robert Frank’s The Americans or even William Eggleston’s Guide does not. Whereas Cartier-Bresson confirmed the traditional with his painterly eye, Frank and Eggleston signalled the future, their photographs informed by some deeper, darker narratives guided by their outsiders’ eyes. From where we are now standing – and looking – these are the decisive moments in 20th-century photography, their iconoclastic ways of seeing and shaping photography as we now understand it. Can we really say that about The Decisive Moment?